The Bottle

The water bottle is an essential cycling accessory. It comes in a more or less standardized shape and can hold anything from 500 to 1000 ml of liquid, usually a mixture of water, carbohydrates, electrolytes and flavorings. Athletes new to the sport might disregard the importance of the latter and go for a ride with just plain water. If they are unlucky, they will hit the wall a few hours in — the so-called bonk — and crawl to the next cafe, supermarket or gas station to consume sweet sustenance.

Professional teams, on the other hand, have this more or less figured out. The EF pro cycling team churns through 34,000 bottles annually and estimates the whole professional peloton to be somewhere around 630,000 bottles. Numbers like that are caused by the way bottles are used during one-day and stage races. On hot days, bottles with cold water are handed out to the riders, who then pour them over their heads to reduce their body's core temperature and thus allow for better performance on the bike. Emptied bottles, with or without carbohydrates, are then cast to the side of the road or handed out to spectators as souvenirs 1.

Mathieu van der Poel handing out a bottle to a spectator (© Josse Wester)

Most professional teams have a nutrition sponsor that provides bars, gels and drink mixes for bottles. This post will be a breakdown of what and how much should go into a bottle. At the end, I will suggest a cheaper alternative to the, in my opinion overpriced, popular nutrition brands and compare the cost over the course of a year.

Carbohydrates

Gone are the days of training with just water. Today's professional athletes push the limit of their gut as much as the limit of their legs. Absorption rates of 150 grams per hour are not uncommon and require nutritional training. Gradually increasing carbohydrate intake between training sessions accustoms the gut to a more intense fueling strategy. Experimenting with a higher-than-usual intake on race day might end it prematurely on the toilet instead of the finish line.

The recommended carbohydrate intake varies based on exercise duration and intensity:

| Duration [h] | Minimum [g/h] | Recommended [g/h] | Maximum [g/h] |

|---|---|---|---|

| <0.5 | 0 | 10 | 30 |

| 0.5–1 | 0 | 20 | 50 |

| 1–1.5 | 20 | 30 | 70 |

| 1.5–2 | 40 | 60 | 90 |

| 2–2.5 | 50 | 80 | 120 |

| 2.5–3 | 60 | 90 | 120–150 |

| 3–6 | 75 | 100 | 120–150 |

| >6 | 75 | 90 | 90 |

Recommended carbohydrate intake by Dr. Alex Harrison

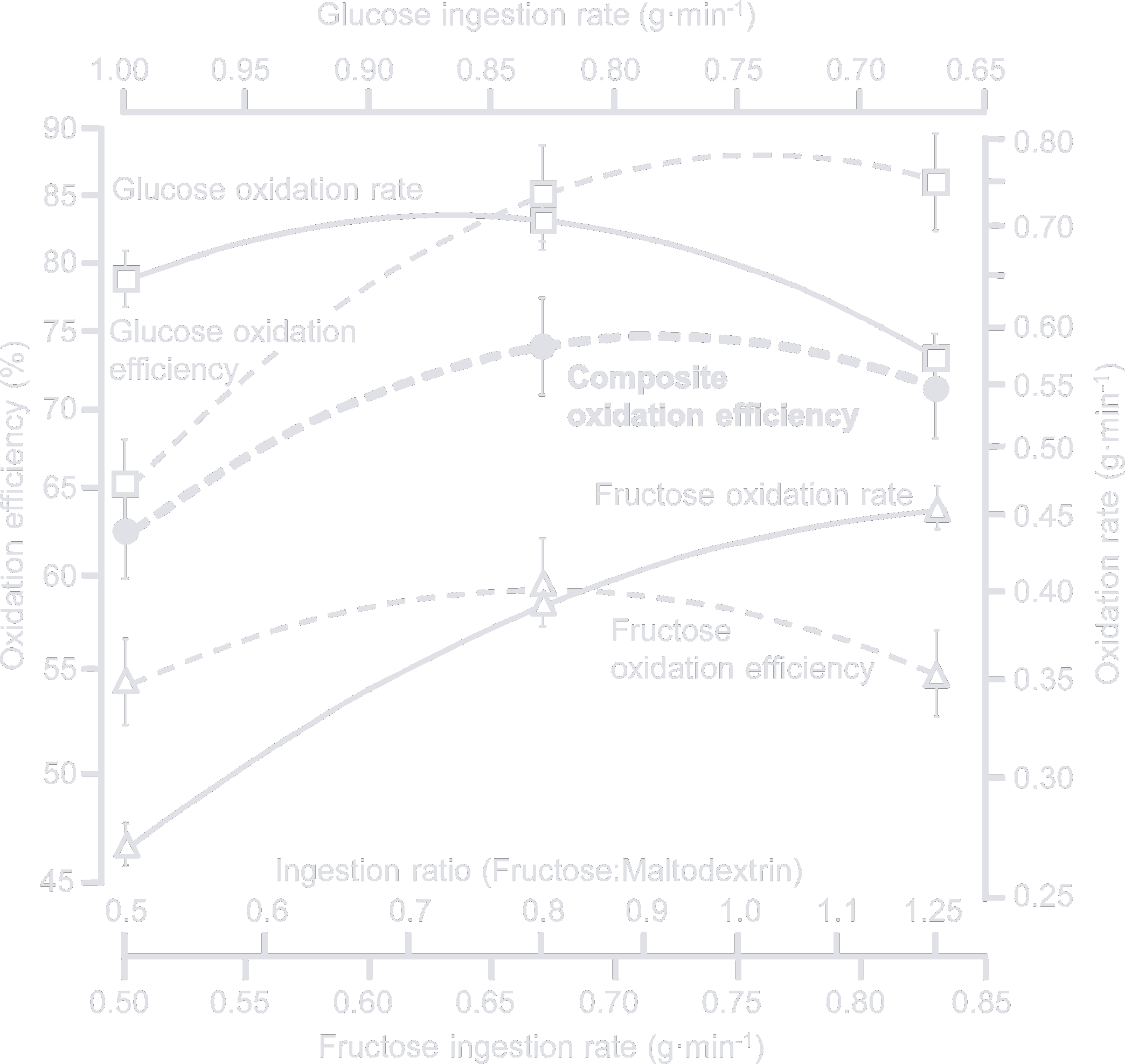

High absorption rates are achieved by mixing glucose and fructose, which are metabolized by different pathways in the body and can thus be stacked on top of each other. In 2013, a study by O'Brien et al. investigated the optimal glucose/fructose ratio and arrived at the following conclusion:

Modeling suggested fructose–maltodextrin–glucose ratios of between 0.8 to unity are oxidized with highest efficiency relative to the ingestion rate. The CHO metabolic responses were associated with a very likely moderate enhancement of mean sprint power with total- and endogenous-CHO oxidation rate, abdominal cramps, and drink sweetness presenting as candidate explanatory mechanisms. Therefore, oral CHO-hydration formulations containing fructose–maltodextrin–glucose at a ratio of around 0.8–1.0 may provide the most practical benefit for endurance athletes.

O'Brien et al.

The popular nutrition brand Science in Sport launched its Beta Fuel drink mix in 2018 with a 2:1 glucose/fructose ratio and reformulated in 2021 to a 1:0.8 ratio, citing the, at this point eight-year-old, O'Brien et al. study. Other known brands like Maurten and MNSTRY offer their own formulations based on a 1:0.8 ratio. It appears to be the magic number everybody is aiming for, even though Figure 4 in the study seems to max out absorption around the 0.9–0.95 mark.

This led me and others like Jesse Coyle and Dr. Alex Harrison to believe that sucrose, also known as table sugar, might be the best option in terms of scientific literature and cost. With an even ratio of glucose to fructose, it is on the other end of the recommended spectrum, but closer to the apparent maximum of 0.95.

Unfortunately, no studies that I am aware of are comparing the absorption rates of sucrose and an equivalent glucose/fructose mixture. If I had to guess, the former would perform slightly worse because the body has to expend a small amount of energy to break up the disaccharide's bond. But this difference is negligible and any mixture in the 0.8 to 1 range will serve you well.

Electrolytes

The other essential part of a bottle is electrolytes. Athletes sweat somewhere between 0.5 and 2 liters per hour. If you have ever mismanaged your electrolyte balance on a hot day, you will never want to do that again. Drinking just water and not replenishing electrolytes will end in cramps and misery.

I experienced this once. The mere act of interrupting the pedaling motion and stopping at a red light caused both my legs to seize up, unable to start when the light turned back green. I had to pause multiple times over 15 km because of random cramps. When I finally got home, I laid down in bed and ate salt straight from the package to stop the endless cramping. Fun times.

Perhaps knowing the composition of sweat would have helped me:

| Element | Concentration [mmol/l] | Atomic mass [u] | Concentration [mg/l] |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sodium | 10–90 | 22.99 | 230–2070 |

| Chlorine | 10–90 | 35.45 | 355–3191 |

| Potassium | 2–8 | 39.10 | 78–313 |

| Calcium | 0.2–2 | 40.08 | 8–80 |

| Magnesium | 0.02–0.4 | 24.31 | 1–10 |

The most important mineral to replenish is sodium. This can be done with table salt, which is around 39% sodium, or more exotic options like sodium citrate, which is around 27% sodium. The reason why one should be preferred over the other will be explained in the chapter on osmolarity.

The amount of sodium lost is determined by sweat rate and sweat sodium concentration. Unless you get them measured, there is no way to know for sure. You can ask yourself the following questions to estimate your fluid and sodium needs:

- Am I a heavy sweater? Heavy sweaters need to drink more.

- Am I a salty sweater? Salty sweaters need to consume more sodium.

I happen to be a heavy, salty sweater — always fun during summer — and aim for around 1500 mg/l. One advantage of mixing your own bottle is that you can add sodium independently of carbohydrates. Salt your bottle to taste like you would your food.

LMNT

But sweat contains more than just sodium. It also consists of other minerals like potassium and magnesium. If you listen to science podcasts, you have probably been bombarded with ads for LMNT, the science-based electrolyte drink mix. Each pack contains 1000 mg sodium, 200 mg potassium and 60 mg magnesium. The reasoning behind this formulation is explained on their website, so I will not repeat it here.

You can make your own LMNT at home for a fraction of the price 2:

- 1000 g sodium chloride (39.3% sodium)

- 150 g potassium chloride (52.4% potassium)

- 150 g magnesium malate (15.5% magnesium)

One gram contains:

- 303 mg sodium

- 61 mg potassium

- 18 mg magnesium

I used this mixture over the last year, paid more attention to fluid intake and had no cramping issues. The taste is better compared to sodium citrate, but I doubt that the added potassium and magnesium have a big impact. Fortunately, electrolytes play a minor role in performance, so I will just stick to what works for now.

Flavorings

Flavorings are personal. I prefer sour over sweet and have always loved the taste of lime. Its acidity and the electrolytes' saltiness balance the sweet sucrose solution. Unfortunately, fresh limes are impractical for frequent bottle preparation or pre-mixed drink mix carried on longer rides. That can be solved by using dehydrated lime powder. The power of a thousand limes condensed into one kilogram.

The problem with that is the limited supply here in Germany. There is one distributor that I know of, and I do not want to reformulate my bottle if they go out of business. The lime powder is also too good to be wasted on a bottle filled to the brim with sucrose. So I searched the internet for a replacement and found one made from different acids:

- 8 parts citric acid (lemon)

- 4 parts malic acid (apple)

- 1 part tartaric acid (grape)

These are widely available and relatively cheap ingredients. Of course, it doesn't taste exactly like the real deal, but it's good enough for training rides. I probably drank well over a thousand liters of it and still like it. Luckily, I don't suffer from flavor fatigue.

Osmolality/Osmolarity

Osmolality and osmolarity are measures that are technically different, but functionally the same for normal use. Whereas osmolality (with an "l") is defined as the number of osmoles (Osm) of solute per kilogram of solvent (osmol/kg or Osm/kg), osmolarity (with an "r") is defined as the number of osmoles of solute per liter (L) of solution (osmol/L or Osm/L). As such, larger numbers indicate a greater concentration of solutes […].

Osmolality and osmolarity are calculated using O = c / M * n 3, where:

cis the solutes mass fraction in g/kg (osmolality) or mass concentration in g/l (osmolarity).Mis the solutes molar mass in g/mol.nis the solutes number of particles in solution. Ionic compounds, such as salts, can dissociate into their ions in solution and therefore contribute multiple particles per molecule.

| Name | Chemical formula | Molar mass [g/mol] | Particles |

|---|---|---|---|

| Glucose | C6H12O6 | 180.16 | 1 |

| Sucrose | C12H22O11 | 342.30 | 1 |

| Sodium chloride | NaCl | 58.44 | 2 (Na+ + Cl-) |

| Sodium citrate | Na3C6H5O7 | 258.07 | 4 (3 Na+ + C6H5O73-) |

It is possible to convert between osmolality and osmolarity using R = L * D, where:

Ris the osmolaRity in Osm/l.Lis the osmolaLity in Osm/kg.Dis the density in kg/l.

To prevent confusion, I will use osmolarity from now on. It makes more sense in a cycling environment, where you work with a limited volume: the bottle. You add carbohydrates, electrolytes and flavorings to it and then fill it with water. The solvent concentrations are measured in g/l, which results in osmolarity.

Maltodextrin

Before we continue with the influence of osmolarity on carbohydrate absorption, let's quickly go over the most important source of glucose in cycling: maltodextrin. It's a glucose polymer produced by partial hydrolysis of starch and unique amongst all other discussed carbohydrates because it comes in different chain lengths. Its chemical formula is C6nH(10n+2)O(5n+1), where n defines the number of glucose units and is 2 < n < 20 4.

Glucose polymers are classified by a dextrose equivalent (DE). The European Union defines maltodextrin to be between 3% and 20%. Polymers below 3% are considered starches, while polymers above 20% are called glucose syrups. The dextrose equivalent can be calculated using DE = 100 * (Mg / Mp), where Mg and Mp are the molar masses of glucose and the glucose polymer, respectively.

Here is a table that shows the correlation between the chain length n and the DE:

| n | Chemical formula | Molar mass [g/mol] | DE [%] |

|---|---|---|---|

| 3 | C18H32O16 | 504.44 | 35.70 |

| 5 | C30H52O26 | 828.72 | 21.73 |

| 10 | C60H102O51 | 1639.43 | 10.99 |

| 15 | C90H152O76 | 2450.13 | 7.35 |

| 19 | C114H192O96 | 3098.69 | 5.81 |

If we assume smaller osmolarities to be superior (foreshadowing), then we would want to go for a maltodextrin with a long chain length/low DE. Unfortunately, it can be quite tricky to find out for consumer-grade products, because they don't need to be labeled and usually aren't. The typical range of commercial maltodextrin I've seen online lies between 5% and 20%.

Carbohydrates

With the theory out of the way, let's continue with something practical. Glucose and fructose are the primary sources of carbohydrates. The former is digested in the small intestine and the latter in the liver. Both must pass through the stomach to reach their destination. Faster passage of the stomach results in better energy availability during exercise. A key factor in that is osmolarity.

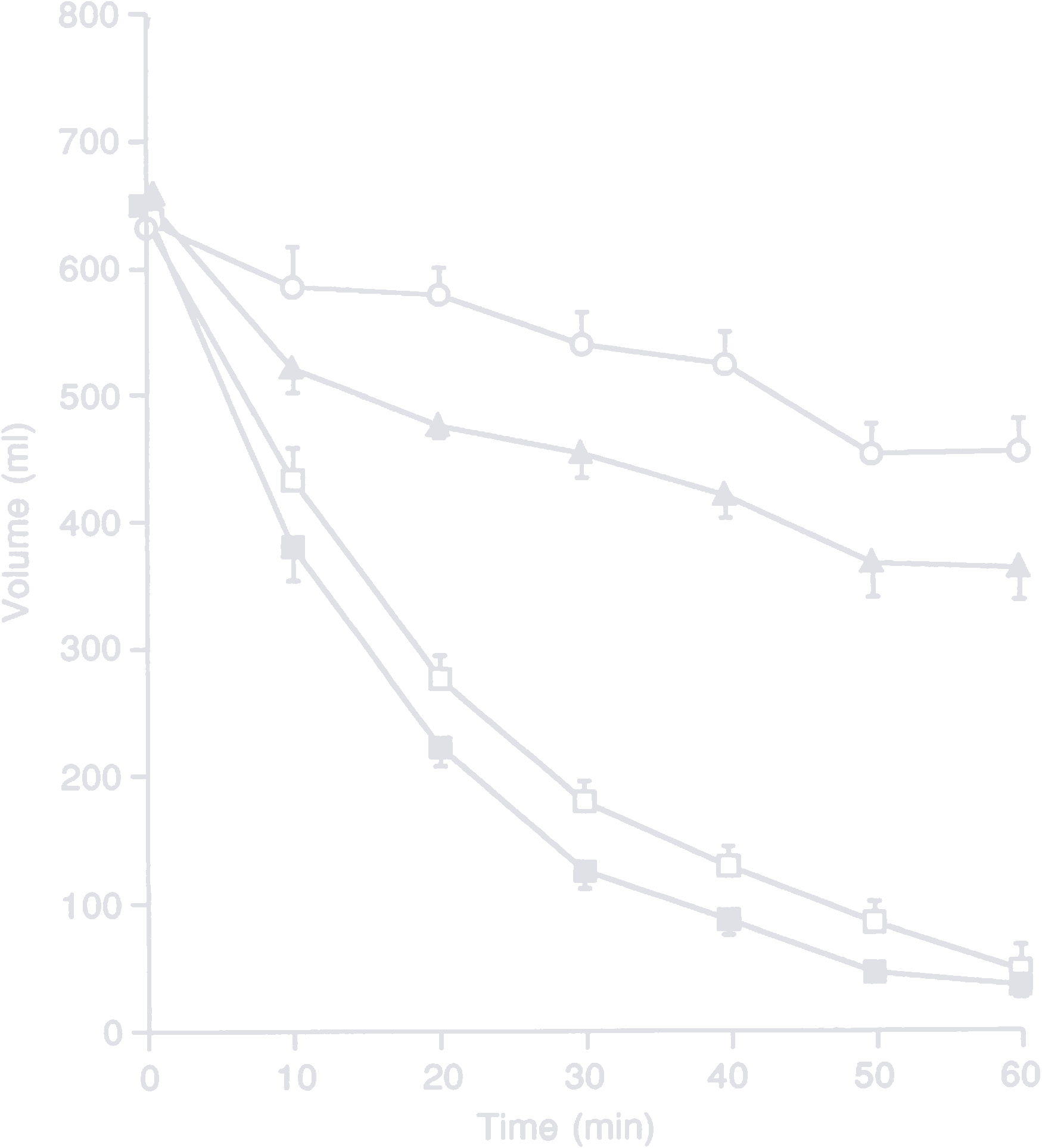

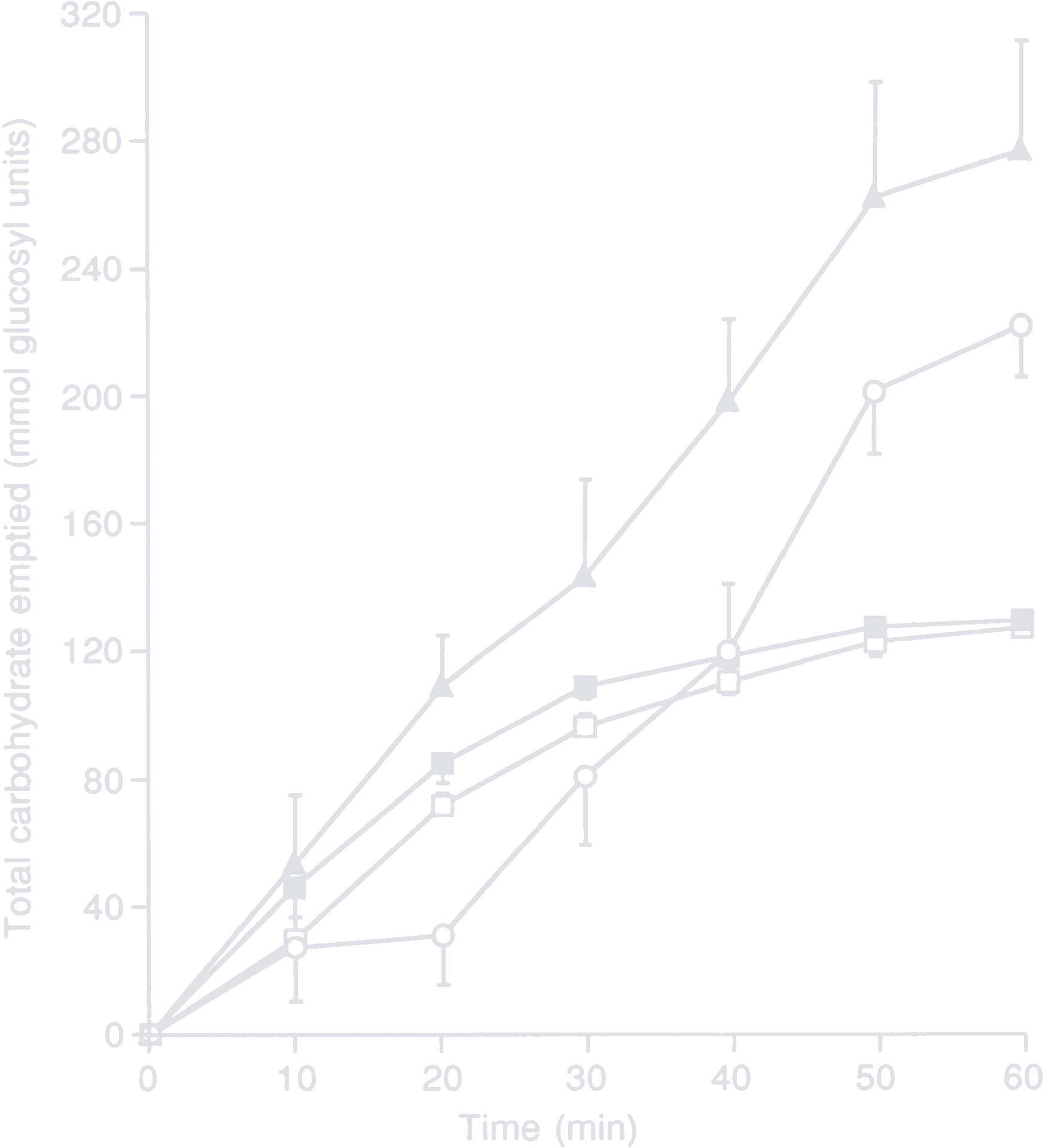

A study by Vist and Maughan explored the effect of osmolarity and carbohydrate content on the rate of gastric emptying of liquids in men. They created four 600 ml test drinks with differing carbohydrate sources and concentrations:

- 40 g/l glucose, 222 mOsm/l (empty rectangle)

- 40 g/l maltodextrin (n = 5), 48 mOsm/l (filled rectangle)

- 188 g/l glucose, 1043 mOsm/l (empty circle)

- 188 g/l maltodextrin (n = 5), 227 mOsm/l (filled triangle)

Total volume remaining in the stomach after ingesting 600 ml of test drink

Total amount of carbohydrates delivered to the small intestine after ingesting 600 ml of test drink

The key takeaways from the study are the following:

- Dilute solutions empty faster than concentrated ones.

- If two solutions have the same concentration, the one with less osmolarity empties faster.

- Concentrated solutions deliver more carbohydrates to the small intestine in the same time.

The first one can be applied universally. Dilute the carbohydrates and electrolytes in your bottle as much as possible/practical. The second one informs the source of carbohydrates in the bottle. Let's say we go for a concentration of 100 g/l, which would not be untypical for a large bottle. There are a few ways to achieve the previously discussed even ratio of glucose to fructose:

| Solution | Osmolarity [mOsm/l] |

|---|---|

| 50 g/l maltodextrin (n = 10) + 50 g/l fructose | 30 + 278 = 308 |

| 50 g/l maltodextrin (n = 15) + 50 g/l fructose | 20 + 278 = 298 |

| 50 g/l maltodextrin (n = 19) + 50 g/l fructose | 16 + 278 = 294 |

| 100 g/l sucrose | 292 |

All solutions have roughly the same osmolarity with a slight advantage for sucrose. As you can see, pure fructose causes most of the osmoles in solution due to its low molar mass. Maltodextrin contributes very little, especially the long-chained version.

The same thing applies when going for a more traditional 2:1 ratio:

| Solution | Osmolarity [mOsm/l] |

|---|---|

| 66 g/l maltodextrin (n = 10) + 33 g/l fructose | 40 + 183 = 214 |

| 66 g/l maltodextrin (n = 15) + 33 g/l fructose | 27 + 183 = 210 |

| 66 g/l maltodextrin (n = 19) + 33 g/l fructose | 21 + 183 = 204 |

| 33 g/l maltodextrin (n = 10) + 66 g/l sucrose | 20 + 193 = 213 |

| 33 g/l maltodextrin (n = 15) + 66 g/l sucrose | 13 + 193 = 206 |

| 33 g/l maltodextrin (n = 19) + 66 g/l sucrose | 11 + 193 = 203 |

Again, all solutions perform roughly the same. The fructose-containing carbohydrate drives most of the osmolarity, while maltodextrin adds next to nothing. Substituting fructose with sucrose seems like a reasonable choice when factoring in cost. The solution's sweetness might differ, but that can be offset with salt and flavorings.

The ratio part of this chapter turned out a little different than expected. I thought I could come up with a simple answer to prefer solution A over solution B, but as demonstrated, if you want a specific glucose to fructose ratio, your stomach will have to tolerate a certain osmolarity. You can always dilute the solution to reduce it.

Electrolytes

Salts are a little harder to calculate because they dissociate into their ions in solution:

| Name | Chemical formula | Molar mass [g/mol] | Particles |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sodium chloride | NaCl | 58.44 | 2 (Na+ + Cl-) |

| Potassium chloride | KCl | 74.55 | 2 (K+ + Cl-) |

| Magnesium malate | C4H4MgO5 | 156.38 | 2 (Mg2+ + C4H4O52-) |

| Sodium citrate | Na3C6H5O7 | 258.07 | 4 (3 Na+ + C6H5O73-) |

Let's calculate the osmolarity for a realistic sodium requirement of 1500 mg/l:

| Solution | Osmolarity [mOsm/l] |

|---|---|

| 3.82 g/l sodium chloride | 132 |

| 5.00 g/l LMNT (3.85 g/l Na + 0.58 g/l K + 0.58 g/l Mg) | 132 + 15 + 7 = 154 |

| 5.55 g/l sodium citrate | 86 |

I think the osmolarities are insane. 4 g of sodium chloride (137 mOsm/l) contributes almost as much as 50 g of sucrose (146 mOsm/l). That's because the sodium chloride molecule is small to begin with, and it even has the audacity to dissociate into two ions. Rude. Here the alternative of sodium citrate is clearly superior if you can stand the taste.

Tonicity

The last reason to care about the osmolarity of your bottle is tonicity. It is defined relative to the one of blood plasma at ~300 mOsm/l:

- Hypotonic: lower osmolarity than plasma.

- Isotonic: same osmolarity as plasma.

- Hypertonic: higher osmolarity than plasma.

Here are some examples of popular soft and sports drinks:

| Name | Osmolality [mOsm/kg] | Density [kg/l] | Osmolarity [mOsm/l] |

|---|---|---|---|

| Isostar | 312 | 1.03 | 320 |

| Gatorade | 353 | 1.03 | 363 |

| Powerade | 368 | 1.03 | 378 |

| Fanta | 415 | 1.04 | 432 |

| Sprite | 479 | 1.04 | 498 |

| Coke | 493 | 1.04 | 513 |

| Red Bull | 601 | 1.04 | 625 |

| Fruit juice | 724 | 1.06 | 767 |

Based on a study by Mettler et al. and densities

A well-prepared bottle is unlikely to be hypo- or isotonic because its purpose in cycling is fueling instead of hydration. However, preventing it from becoming too hypertonic will save you a whole lot of gastrointestinal (GI) discomfort. A study by Rehrer et al. investigated the relationship between GI complaints and dietary intake in triathletes and came to the conclusion that ingesting highly hypertonic beverages correlated with more GI distress

Ingesting hypertonic solutions causes your body to draw water from the tissue and blood into the intestinal tract to dilute the concentration. This is called hypertonic dehydration, or hypernatremia, and it prevents you from feeling hydrated even though you are drinking fluid. The diluted solution then enters the bowel, and if it is not fully absorbed there, water remains in the bowel, which leads to a fun thing called osmotic diarrhea.

Understanding the link between ingesting too hypertonic solutions and osmotic diarrhea wasn't easy. At one point it was 23:00 on a Monday night. I opened a website and was greeted by a calming, dark blue background titled "Evaluation of Diarrhea", a 129-page presentation, and thought to myself: "What the fuck am I doing here. Time to go to bed."

But some of the best insights into this topic came from a recent podcast episode of Peter Attias Drive, where he interviewed Olav Aleksander Bu, the coach of the world-famous triathletes Gustav Iden and Kristian Blummenfelt. He mentioned that his athletes consume up to 240 g per hour diluted with a minimum of 1.4 liters of water. Assuming an even glucose/fructose ratio, that's an osmolarity of ~500 mOsm/l from just carbohydrates alone. Tolerating such amounts requires serious nutritional training, and even with that, they are known to vomit during competition.

The Alternative

I am neither a professional athlete nor an influencer with a nutrition sponsor. I have to buy everything myself. And even though I earn well, I don't like spending money on unnecessary things, an expensive drink mix being one of them. I leave my house with two bottles of the following composition:

- 900 ml water

- 80 g sucrose (€0.08, €1/kg)

- 5 g LMNT (€0.04, €8/kg)

- 5 g flavorings (€0.05, €9/kg)

It has served me well over the last year. No bonks caused by underfueling or cramps caused by electrolyte loss. Is it significantly better or worse than commercial products? Probably not. Are there minor differences? Probably. But if these minor differences are worth the uptick in price is up for you to decide:

| Drink mix | Day (160 g) [€] | Month (20 × 160 g) [€] | Year (240 × 160g) [€] |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mine | 0.34 | 6.80 | 81.60 |

| HSN Evocarbs 2.0 | 0.93 | 18.60 | 223.20 |

| Powerbar IsoActive | 3.51 | 70.20 | 842.40 |

| MNSTRY Fast Carb | 5.42 | 108.48 | 1301.76 |

| SIS Beta Fuel | 6.00 | 120.00 | 1440.00 |

| Maurten Drink Mix 320 | 6.71 | 134.11 | 1609.37 |

Conclusion

That's it. More than you ever wanted to know about carbohydrates, electrolytes and osmolarity. The key takeaways of this post are:

- The purpose of a bottle is fueling and not hydration.

- Train your body to tolerate as much carbohydrates as possible.

- Use a glucose/fructose ratio between 0.8 and 1.

- Consume sodium based on your sweat rate and sweat sodium concentration.

- Dilute the solution as much as possible/practical.

Of course, there are other things to consider if you want to improve your performance. Supplements like caffeine, beta alanine and bicarbonate have shown measurable and consistent results. But that's a topic for another day.

Appendix

The Gel Alternative

Another interesting spin on the "affordable nutrition" topic is the soft flask. It's usually used for running, where half-empty bottles splash around and are annoying. I use one of those:

It's surprising how much energy you can pack into a volume of 150 ml:

- 150 g sucrose

- 75 ml water

- 5 g LMNT

- 5 g flavorings

The water/sucrose ratio is right on the edge of solubility. You need to heat the solution to fully dissolve it. If you add a little more, it won't dissolve. The resulting syrup contains more carbohydrates than three large energy gels.

The soft flask format also offers a much better user experience:

- Reusable with no plastic waste.

- No need to open it with your teeth. It's open all the time. Just take a sip.

- Drink as much as you need. Ever put a half-empty gel back into your jersey pocket and went back for a sweet surprise?

Companion App

The last and probably most useful thing to come out of this post is the companion app. There, you can recreate your bottle and see the glucose/fructose ratio, electrolyte contents and the resulting osmolarity with comparison values. You can experiment and find the best possible bottle composition for your needs.

In 2021, the UCI cracked down on littering:

Riders may not jettison food, bonk-bags, feeding bottles, clothes, etc. outside of the litter zones provided by the organiser. The rider must safely and exclusively deposit their waste on the sides of the road in the litter zones provided by the organiser.

UCI regulation 2.2.025

The rule prohibited riders from handing out bottles to spectators. After a few fines and outrage from the public, the UCI added a special provision:

↩︎Riders are only permitted to give their water bottles to spectators on climbs in the last 50 kilometres of the event or stages. Riders must ensure that the throwing of their water bottles to the public does not present any danger […].

UCI special provision for littering no. 2

The unflavored version of LMNT costs €1.5 per 3.5 g pack (€429/kg). My version, which uses the same components in the same ratio, comes in at around €8/kg. The price some people are willing to pay is insane.↩︎

The complete formula also takes the osmotic coefficient into consideration, which characterizes the deviation of a solvent from ideal behavior. But that is taking it too far for this post.↩︎

I was unable to find the original source of this claim, but it can be found everywhere in the literature. I am skeptical because it doesn't work out when looking at the dextrose equivalent.↩︎